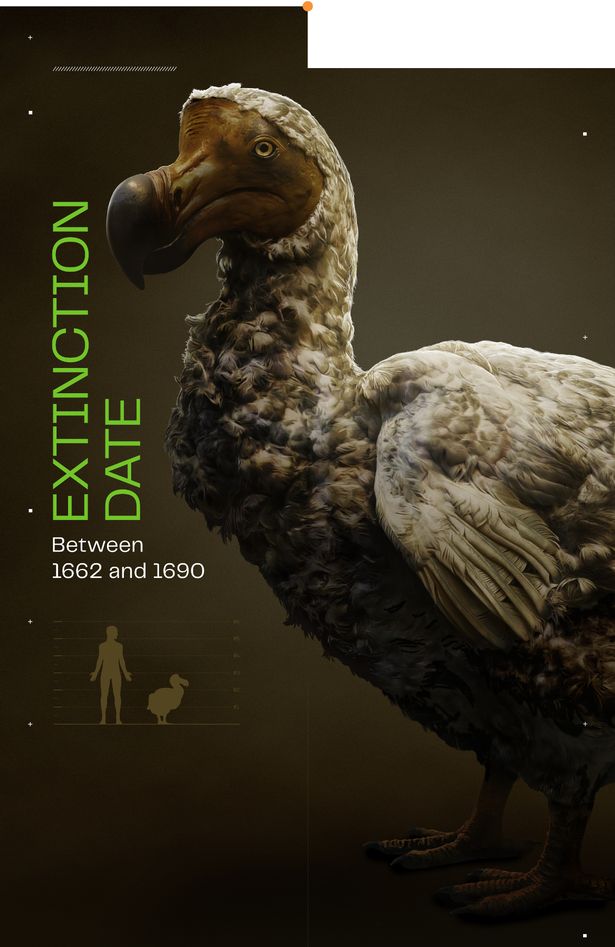

The dodo could once again roam the earth after a de-extinction company announced ambitious plans to bring the long-gone bird back to life 300 years after it was wiped out.

A de-extinction company has announced plans to bring back the dodo more than 300 years after the creature was wiped out.

Colossal Biosciences, who previously vowed to resurrect mammoths and Tasmanian tigers, revealed yesterday (January 31) that the flightless bird would join the roster of long-dead creatures being brought back to life.

“This announcement is really just the start of this project,” says Beth Shapiro, lead paleogeneticist and a scientific advisory board member at Colossal Biosciences who has been studying the dodo for decades.

It remains to be seen whether the re-creation of the dodo is an actual scientific possibility – however with an additional $150m in investments and a new Avian Genomics Group behind them, Colossal Biosciences is ready to give it a go.

In 2002, Shapiro revealed she and her team had extracted a tiny piece of the bird’s DNA, revealing the dodo’s closest living relative – the Nicobar pigeon, native to the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in India.

Last year, after twenty years of research, she announced her team had managed to reconstruct the dodo’s entire genome – the entire set of DNA instructions found in a cell.

But despite these exciting developments, the proposal still throws up questions.

Re-creating the dodo will likely involve genetically engineering a close living relative’s genome so that it resembles the dodo.

The new genome would then be put into an egg cell of the close relative species and implanted into a surrogate mother.

Once the creature is born, it would have to be brought up under very specific conditions, ensuring it has all the care and nutritious food it needs to thrive.

Shapiro explained: “The final version of the dodo will emerge from a pigeon that has been engineered to be the size of a dodo.”

This will be a lengthy process and Colossal Biosciences co-founder said the company is still “nowhere near ready to start implanting embryos into surrogates,” but the company is making headway on developing the necessary technology to make their ideas a reality.

The company could hit another wall as Shapiro explained that, unlike mammals, “we can’t clone birds”.

“There is no access to a bird egg cell at the same developmental time as there is for a mammal,” she explained.

Once the creature is born, more questions arise.

The dodo, which was wiped out by humans in the late 1600s, has no natural habitat to speak of anymore and with no other dodos to learn its behaviour from, the creature won’t be able to learn its behaviour from its parents and peers the same way the original dodo would have.

But Shapiro reckons the new-fangled dodo could thrive in Mauritius and the surrounding islands.

“A goal here is to create an animal that can be physically and psychologically well in the environment in which it lives,” Shapiro added.

“If we are going to bring back something that’s functionally equivalent to a dodo, then we will have to find, identify or create habitats in which they’re able to survive.”